What Did D.W. Griffith Invent? - An Essay on Innovations and Myth in American Film Art

Pictures That Move #19

What did David Wark Griffith (1875-1948) invent? To quote that fabulous line from Ridley Scott’s Kingdom of Heaven (2005), when Christian Crusader Balian of Ibelin (Orlando Bloom) asks Saladin (Ghassan Massoud), what is Jerusalem worth, the victorious Muslim military leader replies: “Nothing … everything”.

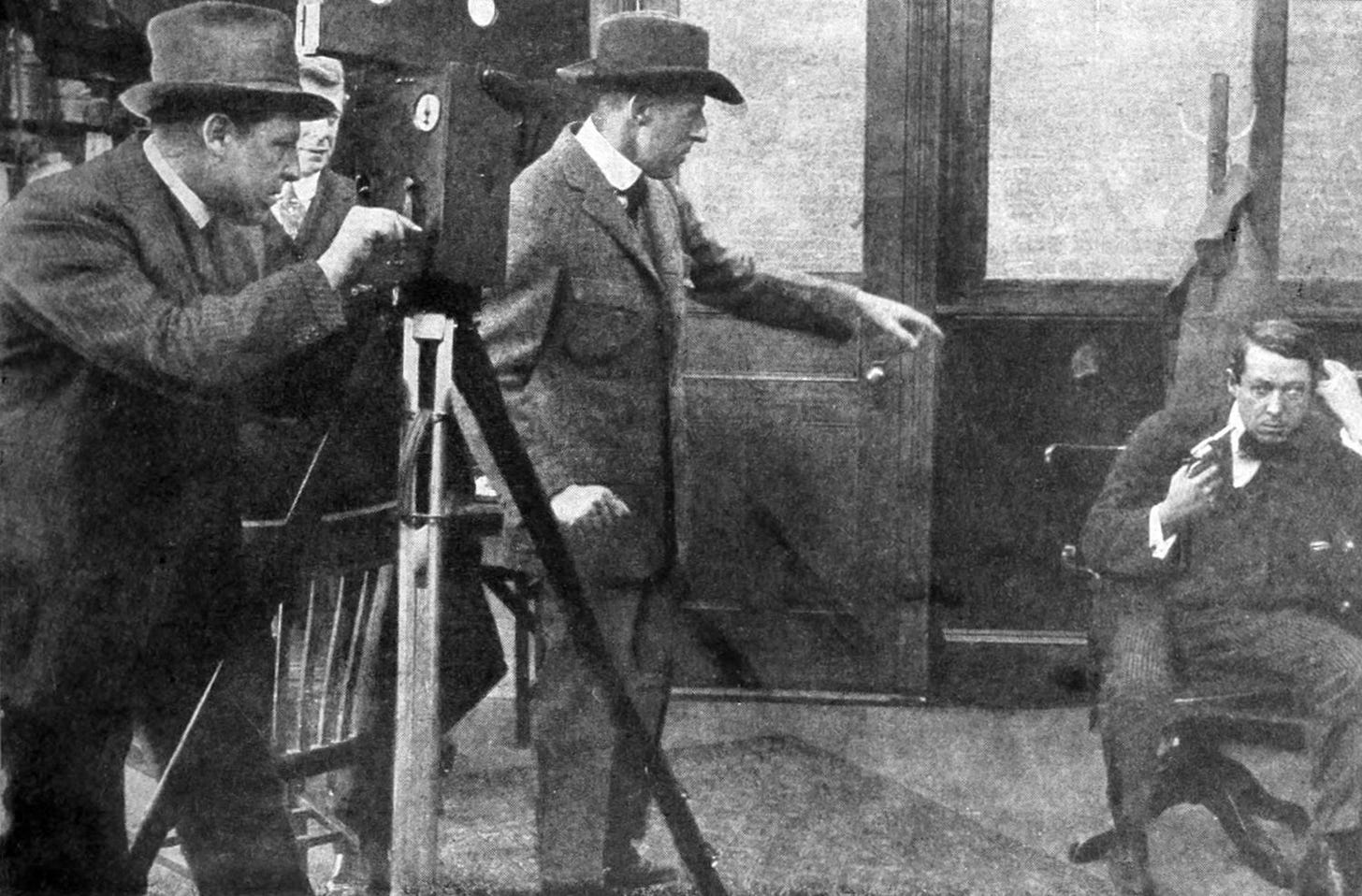

Griffith first and foremost was an innovator, not an inventor. Inventor is entirely the wrong word to use. Most basic film grammar came out of the gates in the 1900s, if not before, all in rough-as-assholes form, but it wasn’t formalised into the coherent form it would become, in large part because of Griffith’s intuitive artistic impulses and transposing certain facets of popular literature and the theatre into film. Some of his innovations have stood the test of time and are used to this very day. This is especially true around the release of The Birth of a Nation (1915), a film which boasts a complex legacy, but which I feel ended a period of the American screen - its so-called primitive era. While Intolerance, I always say, was cinema’s first modern work; its first great experiment in playing around with time. Griffith was hugely influential on the generations after him. He is a colossus.

Via trial and error, and slowly whittling things into shape, he gave American film a certain photographic beauty and quality and the stories came with an increased attention to tempo (especially his home invasion thrillers or chases). He became rather fond of simultaneous action, what we’d call cross-cutting, again to create dramatic momentum. This hit its zenith with the 1916 spectacle, Intolerance (one of my all time favourite films and still a marvel 109 years after its release).

Also, he made so many damn films (over 400 in the space of five years: 1908-1913). Griffith was able to refine, redraw, redevelop, reshape and finally cement the rules of American cinematic narrative, montage and performance. He turned Biograph into a brand known for top quality productions. But Biograph could not contain his ambitions for the motion picture.

Before Griffith, the most important filmmaker in America was undoubtedly Edwin S. Porter (1870-1941), whose two films, The Great Train Robbery (1903) and Life of an American Fireman (also 1903), made for the Edison Company Porter, for all his knowledge of cameras, he was not an artist. In other words, he lacked the creative impulse to expand the scenario written down and give it certain artistic flourishes and grace notes. Griffith possessed this crucial impulse. Porter however does hold his enigmatic place in the development of the American cinema. In those two films mentioned we can see tools and techniques supposedly “invented” by Griffith. Coincidentally, Griffith, who started out in the film business briefly as an actor, actually starred in a film directed by Porter, 1908’s Rescued from an Eagle’s Nest, at Edison. But the company had no further use for Griffith as an actor, so he knocked on doors elsewhere.

Filmmakers in this era would shoot people in full. Like they were on stage in the theatre. The camera composition copied the proscenium arch of the stage. Now this would later have a theoretic and aesthetic value, but that’s not what I mean. The camera shot stories and actors as if it were copying the stage space. It’s how they thought, in the main. Any deviations, such as the close-up, etc., they were not thought out as forming a large visual schema. Griffith ended up formulating the visual schema, more or less.

Griffith in time began to break up the space and use different kinds of shots. Again, he didn’t invent anything, but his keen intuition and artistic ambitions began to make his work more sophisticated than what was around. Not to disparage other companies. Edison’s films could look grand. Check out The Land Beyond the Sunset (1912), directed by Harold M. Shaw (1877-1926). There are some gorgeously atmospheric shots in that.

Griffith transposed things such as theatrical effects lighting he knew from the theatre to the screen and sort out all kinds of literary texts to adapt in order to make movies a legitimate art form of the 20th century. He was fond of specific writers, and paid a lot of money for rights to make films from their work. In time, Griffith made his competitors look stilted and the work became lauded for its technical and aesthetic prowess.

To highlight how he was perceived by the public, here is an extract from a piece written for Photoplay magazine in June 1916, the director bathing in the controversial success of The Birth of a Nation. It is hagiographic (he’s compared to Galileo and Tolstoy, at one point), but neither is it exactly untrue, in terms of what Griffith was: an innovator.

This article puts across, when this man of the theatre (he began his professional life as an actor and playwright named Laurence Griffith) first saw moving pictures, he was appalled at how basic they were and that he had to drag them into respectability. But it also detailed how it was relatively slow-going. We can also deduce this from following the trajectory of his Biograph films.

“He discovered a world of moving pictures; puerile, vulgarly debasing in their triviality; an entertainment one degree removed from a magic lantern show; a passing joke that was novelly attractive as dime museums formerly attracted, and as the melodramas of ‘Theodore Kremer and Owen Davis had previously attracted; sustenance for the people who gape, and first aids to the yawn. That moving picture sphere in the universe of banalities received him coldly, apprehensively, as if it foresaw its dissolution into fertilizer for Art, thought, genius. But he was a sane genius: ambition requires a meal ticket quite as actually as does commonplace contentment. So he at first only slightly punctured with his sword-like genius the armor of stupidity he found encasing picture-making, and his first work was the direction of a “moving picture.”’1

In a piece I wrote recently, exploring how my love of silent films developed, I said Griffith was cinema’s first genius. And I also said it was limited genius, but genius regardless. And I stand by that. Once others copied his established methods and ran off in all directions, the rest is Hollywood. Here’s a few testimonials from major American and foreign directors who came in his wake:

Allan Dwan:

“I had to learn from the screen. I had no other model…The only man I ever watched was Griffith and I just did what he did. It was a wonderful, successful thing to do. I’d see his pictures and go back and make them at my company… Biograph was by many miles the best and the most popular because of Griffith. His pictures had good photography, good lighting, good everything and by watching what he was doing, you learned. We were completely alone you see – there was nobody to talk to, no one to compare with.”2

Cecil B. DeMille (who nails it):

“He was the teacher of us all. Not a picture has been made since his time that does not bear some trace of his influence. He did not invent the close-up or some of the other devices with which he has sometimes been credited, but he discovered and he taught everyone else how to use them for more beautiful effect and better story telling on the screen.”3

Raoul Walsh:

“D.W. Griffith was a genius when it came to making a motion picture. He was a quiet man, almost shy until he picked up a megaphone. He called every male member of the company ‘Mister’ and discouraged familiarity. Some of his biographers have accused him of arrogance and unfairness for being ‘Mr. Unapproachable.’ I always found him ready to listen to opinions, and he was the first to offer help when any of his people got into trouble. Whenever I had the chance, I watched while he directed, and tried to remember everything he said and did. Not many people are lucky enough to have a genius for a teacher and the lessons were free. All I needed to do was keep my eyes and ears open. Later, when I became a director myself, I profited greatly from the things this master taught me.”4

Griffith’s work for the Biograph Company became renowned for a reason: their aesthetic accomplishments and the qualities they boasted as stories. They were exciting, thrilling, funny, grand, People loved Biograph films because they were classy and readily fulfilled the demands craved by the audience. Griffith pulled Victorian drama into the light of the silver screen and for a time, it wowed.

Fact versus Fiction: What Griffith Did and Didn’t Do

The above advert appeared in December 1913 in The New York Dramatic Mirror.

It was a bit of a fuck-you to Biograph, the company he’d made rich, but who stopped Griffith himself from achieving personal recognition. Like with their policy in not crediting actors, Griffith was not credited as the creative guru behind Biograph films.

When D.W. Griffith left Biograph in 1913, it was over his wanting to make longer films. He’d bumped heads with Biograph brass in the run-up to having contract renewed. He’d gone off to California to make films and it ended up costing them a fortune with the four-reeler, Judith of Bethulia (1913), which was filmed in the San Fernando Valley around the town of Chatsworth. He was told not to take the piss with budgets and running time, but Griffith saw American film’s future and it was not one-reel movies (which were kept around for comedy shorts). But dramatic films needed to go large and in the wake of The Birth of a Nation’s release in 1915, one-reelers looked archaic almost immediately . D.W. Griffith did not invent the feature length movie, but he legitimised the concept by making a fuck ton of moola, and Hollywood became the epicentre of the film world because of it. Judith of Bethulia was both an end and a beginning. The Birth of a Nation was both an end and a beginning.

Years later, several American critics, such as James Agee and Bosley Crowther reassessed the Biograph era and said the following:

Crowther:

“With his cameraman, G.W. (Billy) Bitzer, he had learned to move his camera around and shoot a scene from more than one angle. He had worked out the use of the close-up. More important, he developed unusual ways of assembling shots and scenes to build up narrative continuity with cumulative force.”5

Agee:

“Aside from his talent or genius as an inventor and artist, he was all heart; and ruinous as his excesses sometimes were in that respect, they were inseparable from his virtues, and small beside them.”6

The advertisement says Griffith invented the CLOSE-UP. That is not true.

Close-ups were around since 1894, with such film experiments as Fred Ott’s Sneeze or The Big Swallow (1901). This wee film by Edison camera technician and later Biograph co-founder, William Dickerson.

Griffith did use close-ups in certain situations and later in his feature-length productions, he became the master of the close-up. But the inventor? No chance.

Did Griffith invent THE ESTABLISHING SHOT? Again, nope.

Griffith and G.W. Bitzer, his trusty cameraman, certainly began to experiment with atmospheric establishing shots, but the idea they invented them is total bunk.

CROSS-CUTTING? Again, no sir.

What Griffith did do - and wonderfully - was utilise it (inspired by Dickens) to expressly serve the drama of the story and create suspense in a way that marked him out from the crowd. This is a tool he popularised by developing it more fully than had been seen in the past, including in Porter’s The Great Train Robbery, so no, he wasn’t the first to use it. As far as we know, the first instance of the flashback in cinema is Ferdinand Zecca’s 1901 film, The History of a Crime.

STYLISED LIGHTING?

Cecil B. DeMille referred to chiaroscuro lighting as “Rembrandt lighting” and while Griffith and G.W. Bitzer made major strides in this department, Griffith being inspired by theatrical lighting effects, artificial indoor lighting in film was in its infancy, so it took a bit of time. In terms of atmospheric exterior photography, Griffith soon realised it was an effective tool in storytelling.

THE TRACKING SHOT

Griffith did not invent the tracking shot. He used camera movement sparingly in his Biograph days.

WHAT ABOUT EDITING?

Griffith over the course of his five years at Biograph began to create more sophisticated narratives by creating contrasts between scenes and shots. Not just in something exciting, such as the thriller The Lonedale Operator (1912), with its finale featuring sixty-something individual shots, but one of his first masterworks: A Corner in Wheat (1909). This film uses the rich and the poor to create contrast between living standards and social commentary regarding how the actions of the wealthy cause harm to the working class. I wanted to use A Corner in Wheat as an example, because it really is a wee masterpiece and showcases Griffith’s forays in montage well. I highly recommend you watch it.

We can see around this time, Griffith was increasingly aware of tempo, shot length and shot relation. It wasn’t just a string of scenes put together, but carefully constructed for maximum effect and made out of the rhythm of shots to convey drama.

Of course Griffith would reach his montage zenith during the climax of Intolerance, where four narratives cross-cut to barnstorming lengths.

Griffith: Cinema’s First Magpie?

Quentin Tarantino is celebrated today for stealing from others. But everybody steals. As Francis Ford Coppola once advised: if you’re going to steal, steal from the best. Griffith began as a director with a major success, The Adventures of Dollie (1908), about a kid stolen by gypsies, but he had to make hundreds of films for the creative genius to emerge. He worked and worked and worked and made it look easy.

Griffith’s genius was for really mining the one-reel film for dramatic purposes by reinventing Victorian dramaturgy for the screen. I’ve said before, he was a genius, and others have called him that, but it was a limited genius, and by the early 1920s, his style of picture making was old hat and he rapidly fell out of fashion even if he worked all the way up to the beginning of the 1930s, when he was put out to pasture.

I think the mythology around him inventing film tools and techniques was always just self-mythologising (how very Hollywood). It was a case of “print the legend” at the behest of fact. Because it was good PR. Still, as I’ve said, the work was lauded because it was genuinely great and made great strides for the American motion picture. G.W. Bitzer and D.W. Griffith were cinema’s first dream team and Griffith also cemented the role of the director as the creative force behind a production.

But he invented next to nothing. And that’s okay. Because what he did do was so much more important, really. He was the American screen’s major innovator in an industry filled with journeymen and camera technicians who dutifully filmed what was written down in the scenario. Griffith didn’t even use scripts. The vision was all in his head … now, that to me is an artist. He was the preeminent film director of the 1900s and into the 1910s. He invented nothing … he invented everything. He was the American screen’s first major filmmaker. Hollywood as we know it wouldn’t exist without him.

Henry Stephen Gordon, D.W. Griffith: His Early Years; His Struggles; His Ambition and Their Achievements, Photoplay, June 1916

Allan Dwan quoted in The Last Pioneer, Peter Bogdanovich, 1970

Cecil B. DeMille quoted in Autobiography, Cecil B. DeMille, 1959

Raoul Walsh, Each Man in His Time, Raoul Walsh, 1974

Bosley Crowther, ‘The Birth of “The Birth of a Nation”,’ The New York Times Sunday Magazine, Feb 1965

James Agee, Agee on Film, 1958