It’s Part Two of my long essay looking at how my passion for silent movies developed. You can read Part One here if you did not read it previously (and if not, why not *shakes fist*). Because starting at Part Two, well that would be confusing. Say, like watching a silent movie beginning at reel 2 …

It was the best of times, and it was the best of times. After getting A Levels, I went to university. I decided to study Film and moved to Manchester. Bright lights, small city. Chief among its delights: some fine Neo-Gothic and Edwardian baroque architecture.

I LOVED my Manchester years. I got up to all sorts of madness. But I mainly lived in the library. I even had a favourite napping spot (right at the back of the ground floor, right side of the building, by the windows with the Mancunian Way rumbling above). I’d pull up a chair, get a big hardback off the shelf, open it, stand it up on the desk, et voila, a nap screen. Do Not Disturb.

At uni, I discovered German Expressionism cinema. I dove into it, discovering the films of Fritz Lang, F.W. Murnau, Paul Leni, and eventually I wrote an essay about how German Expressionist cinema more or less started and ended with Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari (1920) and the films were too varied in style, including photographic, to be all lumped in together. I still hold this view. I think most film movements exist in the head of the critic, and there alone. It’s the history equivalent of trying to make “fetch” happen. Though, I guess, “fetch” does sometimes happen, because we end up using these phrases to describe historical events/movements that are varied and complicated and do we need them to be lumped together? Because trying to make a coherent argument, with strict parameters and firm regulations and whiling away the hours hunting for aesthetic or thematic similarities, to me it’s like trying to fit a cat through a letterbox. It will go in, but unwillingly, and it’ll leave behind a bloody mess. And a dead cat. (By the way, I have nothing against cats. Well, one thing: they’re not dogs.)

But Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari is genuinely expressionistic. I mean, look at the sets designed by artists Hermann Warm, Walter Riemann and Walter Röhrig. The themes too show us how the psychological was really starting to invade cinema in post-war Europe in big and far-reaching ways. The rest is armchair Freudianism.

I saw Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari, and for a kid raised mainly on Hollywood, both old Hollywood and contemporary Hollywood, plus cult movies here and there, Robert Weine’s expressionist nightmare was another, like Un Chien Andalou (see Part One), of those vivid film experiences I knew was majorly important to my understanding of film and film history. The directing is perfunctory, the ending a cop-out, but still, it was a seismic event for world cinema and a singular film (because you can only get away with that shit once - even though they tried again with Robert Weine’s Genuine, 1920, far less successfully, because nobody remembers or cares about it). And for my money, the scene where Conrad Veidt’s somnambulist, Cesare, climbs through the open window and approaches the bed of Jane (Lil Dagover) and carries her away is the birth of horror cinema. It’s the St Peter proclamation in Rome: “on this rock, I will build your church”. Or whatever it was he supposedly said. The movie version of that. Because that film promotes unease in a way that I would describe as modern, compelling and has nothing to do with the ghost train frolics which pass for much of horror cinema. It’s cinema of the weird.

Two side notes:

In May 2024, for my fiancée’s birthday, we went to London for the weekend. We went for a walk around Highgate Cemetery. Which, given I’d previously lived in London for well over a decade, I’d never been to before now. So anyway, screenwriter Carl Mayer (1894-1944), whose credits include Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari and F.W. Murnau’s Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927), is buried there. And we saw his very modest grave. I kept thinking as I looked down on the aged concrete slab set amid overgrown greenery, the remains of the guy in the coffin beneath the soil, he helped co-write two of the most important silent films: one in Germany, and one in America. He also wrote or co-wrote such classics as The Last Laugh (1924) and Four Devils (1928), and did uncredited work on Leni Riefenstahl’s incredible debut, The Blue Light (1932), made before she went off cheerleading for Hitler. I don’t have the photo I took, sadly.

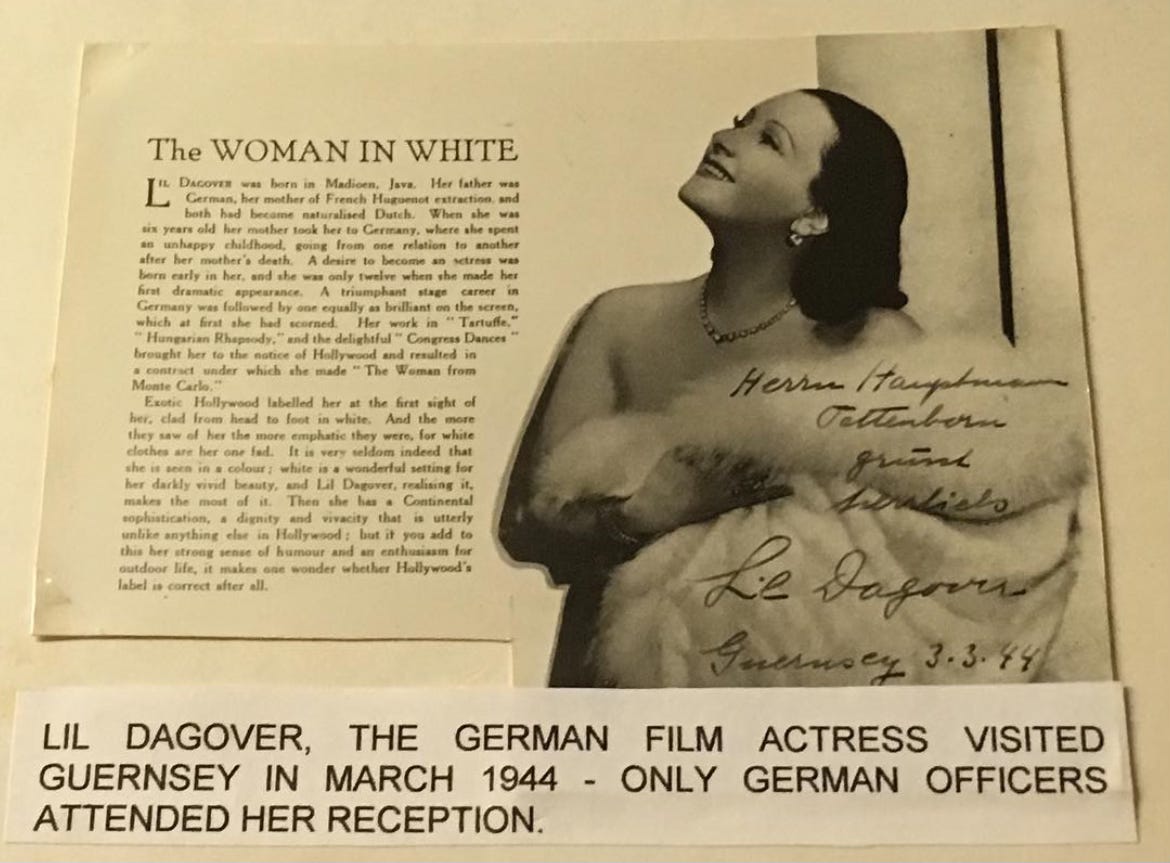

On holiday a few years ago, in the Channel Islands, the island of Guernsey specifically, the wee bailiwick’s museum has photos of Lil Dagover entertaining German troops during WW2 on the island. The Channel Islands being the only part of the British Isles occupied by the Nazis. I also remember they had Nazi napkins on display in a glass cabinet. Talk about branding.

My photos from the war museum in Guernsey (sourced from my Instagram):

Dagover, a major star of the German screen, like Emil Jannings, another big time actor of Weimar era cinema, who also crossed over to Hollywood for a bit and who bought a house on Hollywood Boulevard, which being countryside back then had a chicken coop in the yard facing the street. Jannings won two Oscars (for The Way of All Flesh, 1928 & The Last Command, 1928) before pissing off into the arms of Hitler. I actually saw his Oscar for The Last Command. It’s on display at the film museum in Berlin (a very cool place, the mirror room is super cool). Dagover also had close ties to the Third Reich and was an occasional dinner guest of the Führer’s. To paraphrase the old knight in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade: “They chose … poorly”.

Hollywood Babble On

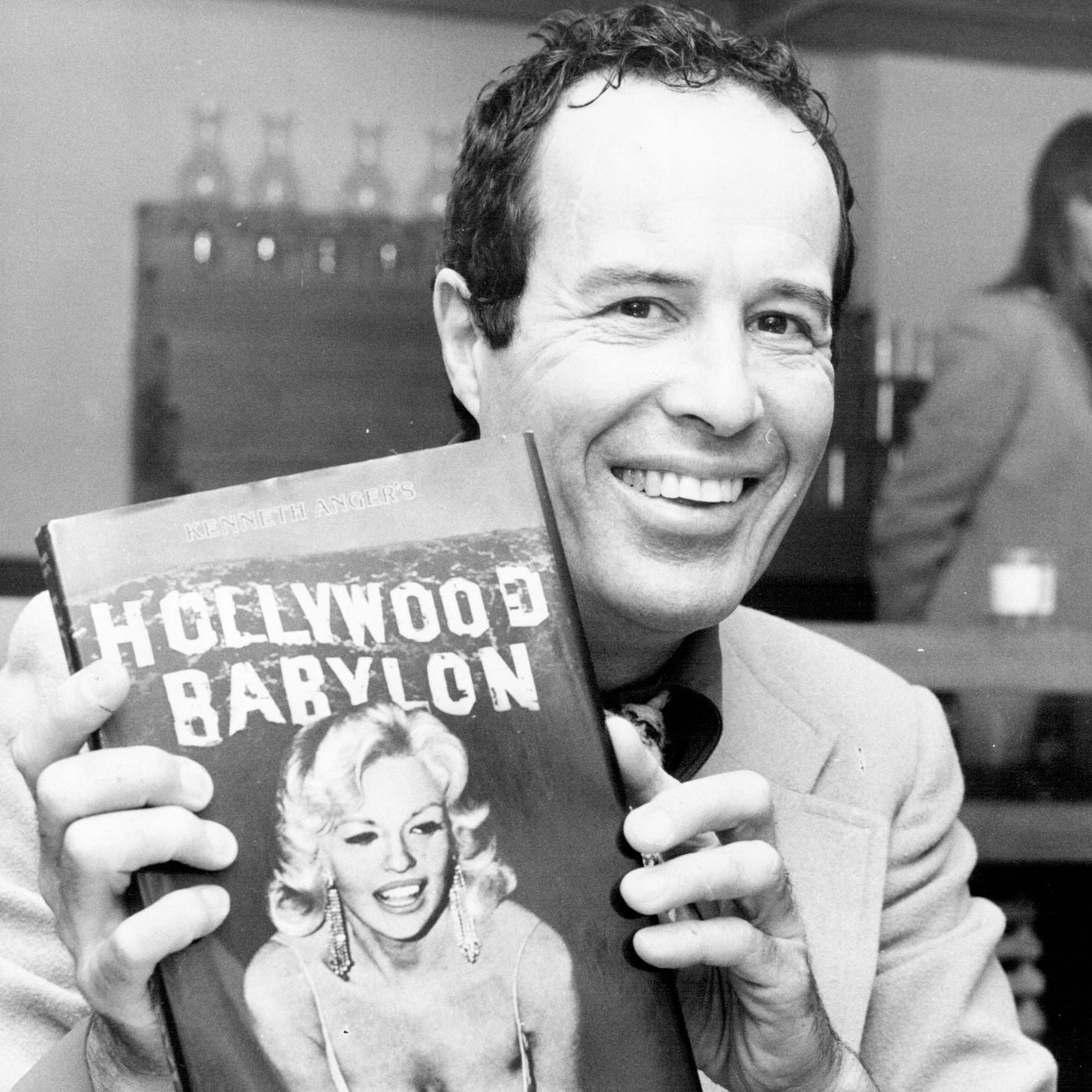

Kenneth Anger’s book Hollywood Babylon (1959) is full of shit, and it is BRILLIANT.

“Welcome to Hollywood - made manic in its heyday by ‘joy powder’ and cocaine-crazed comedies … seduced by vamping heroin heroines … shaken by Fatty Arbuckle’s orgiastic excesses and Errol Flynn’s amoral extravagances … stunned by Marilyn Monroe’s tragic suicide and Sharon Tate’s brutal murder.

“Take a walk down ‘The Boulevard of Broken Dreams,’ where the sex goddesses, the starlets, the matinee idols, the American aristocracy and the Mafia moguls meet.

Here - as it’s never been shown before - is the scalding reality behind the glittering facade of America’s dream factory - the true stories and darkest secrets behind the lurid headlines that have - for more than seven decades - titillated the world and electrified a nation.”

How can you not love that? The blurb is so enticing, right? And I love Anger’s sensationalist and snappy, sometimes mean-spirited, but at the same time affectionate, prose style. And chapter titles such as Heroin Heroines, Chop-Suicide, William Randolph’s Hearse, Fat Man Out.

I genuinely have no memory of how I came to own my copy, or how I’d come across it, but it was during my uni years I’m sure and I devoured it in one sitting. I LOVE this bloody book. It is full of tittle-tattle, slander, nonsense, lies, innuendo and unadulterated baloney. No, DW Griffith wasn’t sleeping with Lillian and Dorothy Gish. No, Fatty Arbuckle wasn’t a sex maniac who defiled a starlet with a coke bottle. No, Ramon Navarro wasn’t killed after having a dildo bequeathed to him decades before by Rudolph Valentino shoved down his throat (the poor guy chocked on his own blood after being beaten up). And no, Valentino’s last words were not about being a pink powder puff. Whatever that means. But who cares about the truth in the city of make believe? Myth is where it’s at, what we’re dealing with. It is storytelling … make believe out of make believe. It really does detail however the overarching theme: Hollywood, there was nowhere like it. To quote Francis Ford Coppola’s description on making Apocalypse Now (1979): “We had too much money, too much equipment, and little by little we went insane.” That was Hollywood in the 1920s before the Code came in. Well, the myth of Hollywood. And myth is important because it creates new stories and new possibilities and new ways of learning about the past. Myth opens forth.

Because Hollywood gave us a new pantheon of beautiful people to worship, Hollywood ditched the Lord and went pagan. Hollywood was the new decadence. The beautiful and the rich lived like the gods of Mount Olympus in the Hollywood hillsides. The stars back then, compare them to Hollywood in 2025. As Jules from Pulp Fiction (1994) says: “same league … hell, it ain’t even the same sport.” The non-entities we have now … man, it’s depressing.

Kenneth Anger was such an amazing bullshit artist (and an incredible director who made Americana erotic). But he was also a terrific peddler of nonsense … like how he claimed on the audio commentary for Scorpio Rising (1963) that a biker died during its filming and that his death was caught on film and there wasn’t there just something poetic about it all. It’s not true. But it’s true to Anger because myth is possibility. He isn’t lying because he’s a pathological liar. He is bending the truth because, like I say, it creates mythology, allure, stories atop stories, it reflects our need for myth, memorialising the lost and finding new things to say about existence and life, reveals new variations on ancient archetypes. Anger’s approach to bending the truth, relating hearsay as fact, gossiping about misfortune, just making shit up off the top of his head, it fits so beautifully into the myth machine of Hollywood itself. One thing I’ll say: Make Hollywood Babylon Again.

This book actually became pivotal to one of my historic murder obsessions that isn’t the Zodiac (man, that’s a whole other kettle of fish): the February 1922 murder of Anglo-Irish William Desmond Taylor (1872-1922), a director for Famous Players-Lasky, and a man who might well have been killed in a crime of passion or a retaliation for a dalliance with a young girl. Either way, it involved, for my two cents worth Mary Miles Minter (1902-1984) and her mother, Charlotte Shelby (the OG when it comes to monstrous movie industry mothers/agents/control freaks). One of those did it. That’s what I reckon. I’ve gone deep on this incident, including going through old newspapers and records and searching out amazing websites crammed with stuff all about the case or adjacent to the case.

I would highly recommend also A Cast of Killers (1986), a book made up of director King Vidor’s research into the murder and written by Sidney D. Kirkpatrick. William Mann’s Tinseltown (2014) is also a riveting read, but apparently there’s a lot of fiction thrown in with the history (make of that what you will). As an aside, on a trip to Hollywood in 2023, I got to see William Desmond Taylor’s niche in the mausoleum at Hollywood Forever Cemetery. His remains rest there under his real name: William Deane-Tanner. I’ll dig out the photo and put it here, one day. I have ADHD, so I bung anything and everything on pen drives and never label them, so I end up with all these pen drives and I don’t know what’s on them and then the thought of having to look through them all … too overwhelming.

Hollywood Babylon really did the trick. Especially its early chapters looking at the birth of an industry as the birth of scandal and the creation of demigods and demigoddesses of the silver screen. Hollywood was actually a very quiet and pleasant country town for the rich elites. Mingled in with the wealthy, who lived there or had summer homes there, were poor farmers scraping by. They most certainly did not have something as uncouth as a movie theatre in Hollywood until much later on.

Today, you can get to Hollywood via numerous roads. It’s only a few miles out from downtown Los Angeles, which, until the 1890s, was a one-horse town with no horse or town. Yes Los Angeles was booming by the 1910s, but it might well have been a million miles away from insular, suspicious and sun-kissed Hollywood (which you could reach via a downtown streetcar). In those days, Hollywood was a laid-back type of town. It hummed to the rhythms of nature. And it was very quiet. In the eve, smudge pots burned to keep the fruit groves from turning bad. Mist would roll through. Further afield, there were oil derricks going kerchunk, kerchunk, kerchunk. Then some crazy kids from back east pitched up with the devil’s tool: movie cameras!

Hollywood appealed because its climate and range of vistas and it was well away from the Trust (who dominated American movies in the earliest days with an iron grip. They had the patents on the cameras and licenses for the films and anybody who broke their rules, they’d send out ruffians with side arms, and they were ordered to shoot the cameras, smash the cameras or take out the film stock and expose it to the sunlight to ruin the day’s work. You should check out Peter Bogdanovich’s Nickelodeon (1976), which is forgotten today, but it details these early years right up to the premiere of The Birth of a Nation (1915), and it is primarily inspired by the stories Hollywood pioneers such as Allan Dwan and Raoul Walsh told the director. I really like the movie, and it deserves more eyeballs.

Hollywood also greatly appealed because all within a short distance you had: the mountains, the beach, the countryside, urban places, endless fucking sunshine. It rains about 30 days of the year in the sunny Southland. And Los Angeles was on the rise as a jewel of the Pacific. D.W. Griffith, that first genius of the screen, also knew Los Angeles, because he’d appeared on stage there in his former life as an actor. He shot the first film ever made in Hollywood itself: 1910’s In Old California. His excursions out to the west coast in winter time helped establish Los Angeles and the San Fernando Valley as the filmmaking base it would become shortly with the arrival of other companies. He wasn’t the first director to make a film in Los Angeles (I’ll write about Hobart Bosworth and The Count of Monte Cristo at some point), but he absolutely took a part in creating the film colony.

Soon the orange groves and Victorian mansions for the snooty folk would give way to clapboard studios and outsiders pitching up more and more to lower the tone. (Hollywood was also a dry town, even before prohibition.) Then “the movies” came. That is the name the Hollywood residents gave to these ragtag band of actors, directors, writers and other industry riffraff: “movies”. In those early days, hoteliers and boarding-houses would have signs up about no dogs and “no movies”. They used it as a collective noun to describe film workers.

No matter how snooty and unwelcoming the townspeople acted, the tide could not be stemmed. Bucolic surroundings became all concrete and commerce, and Hollywood Boulevard, once called Prospect Avenue, transformed from lovely country lane into the boulevard of broken dreams. The movies had invaded, and they colonised the place with lightning efficiency.

If you’re interested in the story of Hollywood as a town, its history from the 1880s to the modern era, then I absolutely recommend Gregory Paul Williams’ The Story of Hollywood: An Illustrated History (2006). The photos are *chef’s kiss*.

Forget it, Joe. It’s Sunset Boulevard

Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard (1950) is not a silent film. But it is another film that furthered my appreciation for the era and it’s also one of my all-time favourite motion pictures. I’ve actually stood outside Joe Gillis’ apartment at the top of Ivar Avenue, and I paid homage to the opening shot of the movie using my iPhone to pan across the street to the Alto Nido Apartments (and I did it without a crane). It’s on my Instagram here.

I adore this movie because Norma Desmond (played to perfection by Gloria Swanson, whose autobiography is superb, FYI), well she’s not wrong in her assessment that talking ruined the universality of the movies and in relying so much on dialogue going forward, I think movie directors lost the ability to tell stories through images alone. I’d say the very best directors working today continue this uniquely cinematic principle. Say, George Miller. You can watch the Mad Max movies with the sound off and the musicality of the images shines through (he was massively inspired by Buster Keaton). Yes, movies used inter-titles to guide the viewer, but they still told stories through moving pictures, and you could understand what was going on (certainly with the best of them).

So, I’m with Norma Desmond, all that talk, talk, talk robbed cinema of its true uniqueness. Because when the image stands alone, when it moves alone, when figures have no need for speaking, we were in the realm of something that was apart. Of course, cinema is an amalgam of other art forms, but like I said, from 1895-1929, when talking pictures took off like a wildfire, there is something so alluring and beautiful and pure about silent movies. Yes, pure. Talking pictures? No, thanks!

We’ve got homes to go to …

I wanted to wrap up my two-part, very informal, essay by summarising.

I discovered silent films at college, seriously gravitated towards them at university, where I discovered silent films from all around the world. Because while Hollywood dominated in the post-WW1 years and gobbled up all the competition, so that Hollywood meant not just quality product - but superior product - we have German Expressionism, Scandinavian cinema, the early epics made in Italy, the Soviet flicks where montage was king, films made Down Under, in Britain, and in Japan, to name a few. It wasn’t all Hollywood (heck, American cinema could even boast its own avant-garde works as early as 1911). But Hollywood’s rapid development and ability to spread its industry far and wide, made it top dog by the 1930s, if not before. Because Hollywood did something the other nations didn’t do or couldn’t do: created a mythology. It sold a dream. Fans mags exploded. Popular culture became big business. Seriously, the movie magazines from this era are wonderfully nuts and obsessive and full of that crucial American staple: the hard sell. Movie stars were pitched as idols and they were idolised accordingly.

In the years since, as I grew up and became a professional film writer (for my sins), I've been fortunate enough to attend plenty of rep screenings at home and abroad. I’ve seen 1920s German mountain films in Berlin, watched an amazing 35mm print of Victor Seastrom’s The Wind (1928) at the BFI, reached peak cinephile watching Abel Gance’s 7-hour Napoleon (1927) at the Royal Festival Hall, with live orchestra conducted by the late Carl Davis (who was married to Jean Bolt from the 1980s sitcom, Bread). If by the end of that film you’re not standing on your chair, hot patriotic French tears streaming down your face and shouting “vive la France!” then why did you come? Because that film’s aesthetic greatness is enough to turn anybody French. Of course I didn’t stand on my chair, shouting “vive la France!” But I did in my heart. IN-MY-HEART!

So yes, I continued my fascination with this unique and beautiful and pioneering stage of cinematic art. Silent movies are my obsession, my passion, my fixation, you name it. I could talk your ears off about them, if you let me. Wait, come back!

In the years since, I’ve kept on reading and viewing, making constant discoveries. I’m soon going to write about one of my favourite films from 1920s France. I would honestly call this particular work a hidden monument. Because it’s a major work of cinematic art, but it’s been forgotten. More on this soon!

I will also perhaps do a list of my all-time favourite silent movies and then larger, formal essays on them in particular. One of my abiding favourites: Erich von Stroheim’s Greed (1924).

Silent movies. I think they deserve love and respect and care. Because around 70 percent of films made in the silent film period didn’t survive. So many films lost like tears in the rain. Time to die. What a tragedy that is.

Until next time!