Pictures That Move has returned! I’ve been on hiatus since early March (for “reasons”), but the focus this week is just about perfect. Aligning as it does, somewhat amusingly, with a recent escapade and a cinematic obsession of mine: the work of Joseph “Buster” Keaton (1895-1966).

One Week (1920), co-directed by Edward F. Cline and Keaton, released 1st September 1920, sees the funnyman building his own flatpack house. One Week sprung immediately to mind as a topic for this week’s entry because it chimed with my own comically inept attempt at DIY.

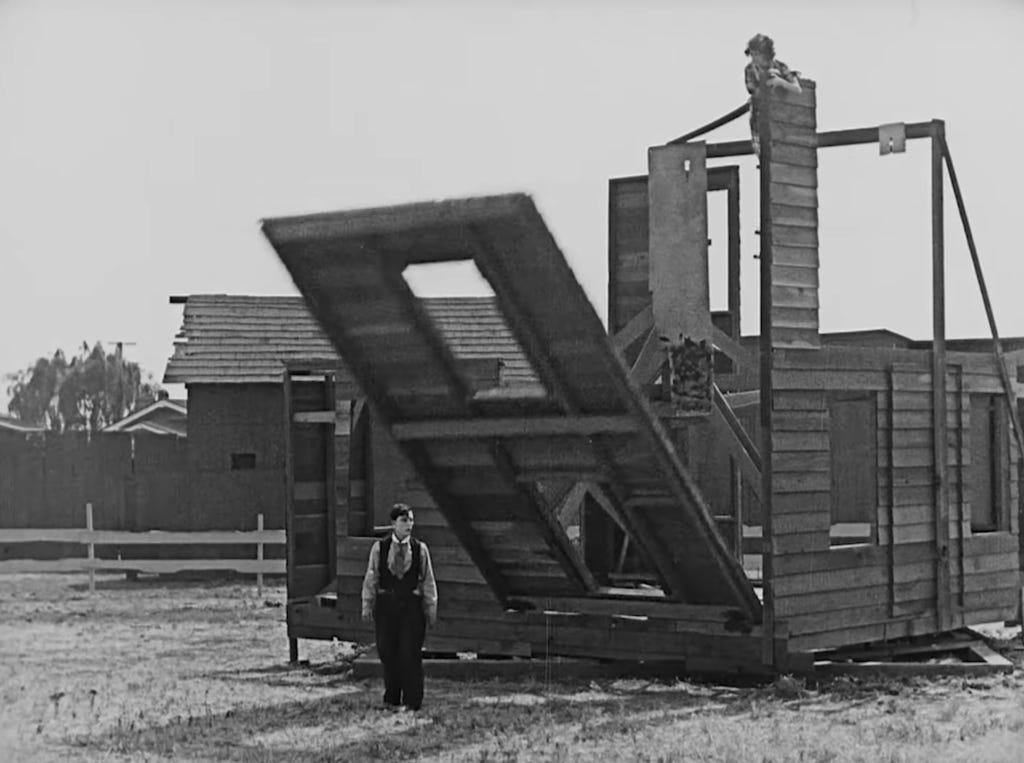

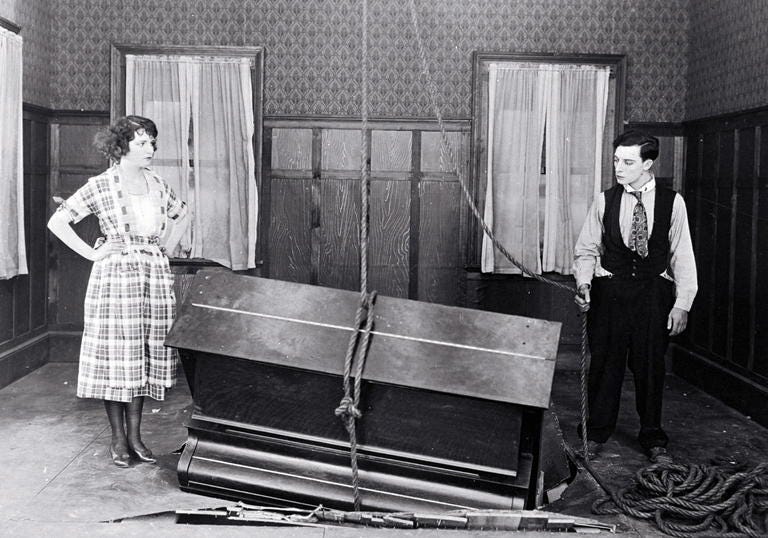

Luckily, I didn’t have to build my own house (but I did put up a clothing rail, with crucial help, which turned into a thoroughly slapstick affair, including breaking a flatscreen television). But if I had to build my own home, it would very likely end up looking like the Cubist monstrosity Keaton and Sybil Seely haphazardly construct (and in doing so violate just about every building code imaginable). There’s a fixer-upper and then there’s … this madness:

One Week, placed on the US Library of Congress National Film Registry list in 2008, is something akin to an urtext for Keaton’s artistically successful indie years. One Week more or less set out the aesthetic vision for Keaton’s style of comedy and cinema, which the director-star played around with and expanded upon during his extraordinary 1920-1928 run. The list of masterworks created in short and feature-length form is astonishing. Then he signed a contract with M-G-M and it all went to the dogs. Robbed of his genius by studio meddling and dictatorial controls, Keaton drank up all the booze in the sunny Southland and beyond and he slowly faded away from the big time as many talented people in Hollywood tended to do when they couldn’t fit into the confines of the studio system.

I’d say the key appeal in Keaton’s films is the delivery of crazy, hair-raising stunts complete with bags of romantic-tinged charm. Repeatedly, he cast himself as a young man struggling to make sense of a madcap situation he finds himself in.

One thing I’ve long-adored especially: how his guileless innocents progress from the befuddled to the heroic. If Chaplin’s Little Tramp tugged the heart-strings as much as made audiences crease with laughter, Keaton offered his own version: the everyman who ends up, entirely by determination and inner grit, and refusal to be defeated, somehow coming off the hero in a fraught, sometimes downright surreal, scenario.

Keaton got the girl, usually anyway, or emerged victorious, though sometimes not, but there typically came something of a sting in the tail - one last gag to beautifully downplay the heroics and renders the hero the luckless again, and therefore humble once again (One Week’s finale contains one of the best visual gags in silent comedy - so I won’t spoil it). Keaton’s wistful motion pictures give us “such is life” shrugs in cinematic form. It is all beautifully balanced, the sweet with the sour, the rough with the smooth, the romantic and the disappointed, the joy with the melancholy.

Also, if you’ve seen 1928’s Steamboat Bill, Jr, you’ll know it boasts arguably the defining image of Keaton’s style of cinema: the façade of a house collapsing, with Keaton stood there helpless and hapless as it falls down on him. His bacon is saved by his whole body passing through a window. If physical comedy is about maths (timing) and engineering (constructing the gag), Keaton was the professor as movie star, the gag man as ingenious engineer. He also retooled the hurricane sequence from One Week, for Steamboat Bill, Jr, FYI. The reworked sequence of the latter is one of the most visually stunning extended sequences of the silent era … maybe any era of the movies. Yes, it’s that good!

But Keaton used the collapsing house façade first in One Week. But its roots can be found in a Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle (1887-1933) short in which Buster also appeared, 1919’s Back Stage. Keaton made it his own and transformed it into an iconic moment in cinema history. The Arbuckle version boasts none of the luckless-hero majesty which shined repeatedly in Keaton’s work.

One Week was Keaton’s first indie production released with producer Joseph M. Schenck (under a distribution deal with Metro Pictures) after striking out on his own (having served his apprenticeship under doomed fatso funnyman Arbuckle, who landed himself, unjustly, in hot water with the press and the film-loving public, thanks to a September 1921 Labor Day party going awry). However, One Week wasn’t Keaton’s first solo effort. That would be The High Sign, released eventually in 1921, and delayed because Keaton was dissatisfied with the results.

Keaton produced many of his classics out of a facility on Lillian Way, which starts off Lexington Avenue and finishes at Melrose Avenue (the former studio can be found a little south off Santa Monica Boulevard at the corner between Lillian Way and Eleanor Avenue). In March 2023, I spent a few days in Hollywood, and went to the former site of the studio and snapped a couple of photos. (And yes, I went to the Chaplin-Keaton-Lloyd alleyway running between Cahuenga Boulevard and Cosmo Avenue).

There’s nothing to see at Lillian Way, not really, but there is a discreet plaque on the pavement commemorating the site. Los Angeles’ shocking disrespect for film history and mania for building and re-building has led to many sites of great importance disappearing beneath concrete and glass.

Back to One Week. What I love the most about this slapstick marvel … what I truly love about the cinema of Keaton … it's just so romantic. Keaton and co-star Seely are downright adorable together on screen. For Keaton is one of cinema’s great romantics. His work is not remotely intellectual despite the fact he attracted the attention - years later - of intellectuals, who found his stone-faced minimalist acting and failures borderline existentialist. In their snooty eyes, he was more suited to their highbrow tastes than the comedy-melodrama style of Charles Chaplin (1889-1977) or the all-American boy shenanigans of Harold Lloyd (1893-1971).

The film is also noted for a cheeky and teasing “breaking the fourth wall” scene, when naked Sybil Seely takes a bath and drops her soap to the floor. The cameraman, ever the gentleman, covers the lens so she can pick it up (without the audience getting an eyeful). It’s a great bit of invention destroying the objective barrier between camera and subject which holds the classical Hollywood film and its storytelling method together.

One Week is featured on Eureka Entertainment’s boxset, Buster Keaton: The Complete Shorts and you can find it here to watch on the YouTube.

Until next time…

I love this movie! I show it to my kids in school and they think it's hilarious, plus I can stop the film and ask stuff like "What is Buster doing now?" and so on. And of course the ending with the trains is always a crowd pleaser!